If you haven’t heard of Air Swimmers before, you probably had a miserable life. Air Swimmers are inflatable foil balloons made in the shape of fish. But what makes them really awesome is the fact that they can be remotely controlled to fly around in a room. One of my friends, Claudio, developed an obsession interest for them; and that’s when we decided to create our own hackuarium.

The idea was simple: buying a bunch of Air Swimmers, hacking into their controllers and running a swarm simulation to control them. If you’re interested in doing the same and you have a basic knowledge of electronics …you’re reading the right post. At the end of this article you can find the links to buy all the necessary components.

How it works…

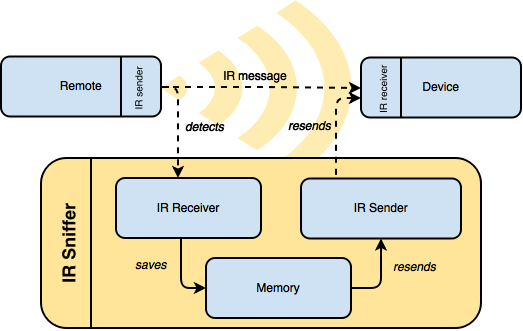

The first step is to understand how the remote controller works. Every controller has an IR sensor and it usually works with a proprietary protocol. We wanted to use a modular approach which enables us to set up new fish with little to no work. For that reason, we decided to sniff the IR packets sent by the remote controller, so that we could then replay them at will.

This technique is often referred as sniffing, since the device we’ll build will detects IR messages which were not originally directed to it. This particular approach works perfectly with the majority of IR remotes and devices, since there is no actual processing involved. Every time you push a button on the remote, you’re sending the same message; the receiver ignores where the message comes from and just executes it.

Step 1: Building the IR receiver

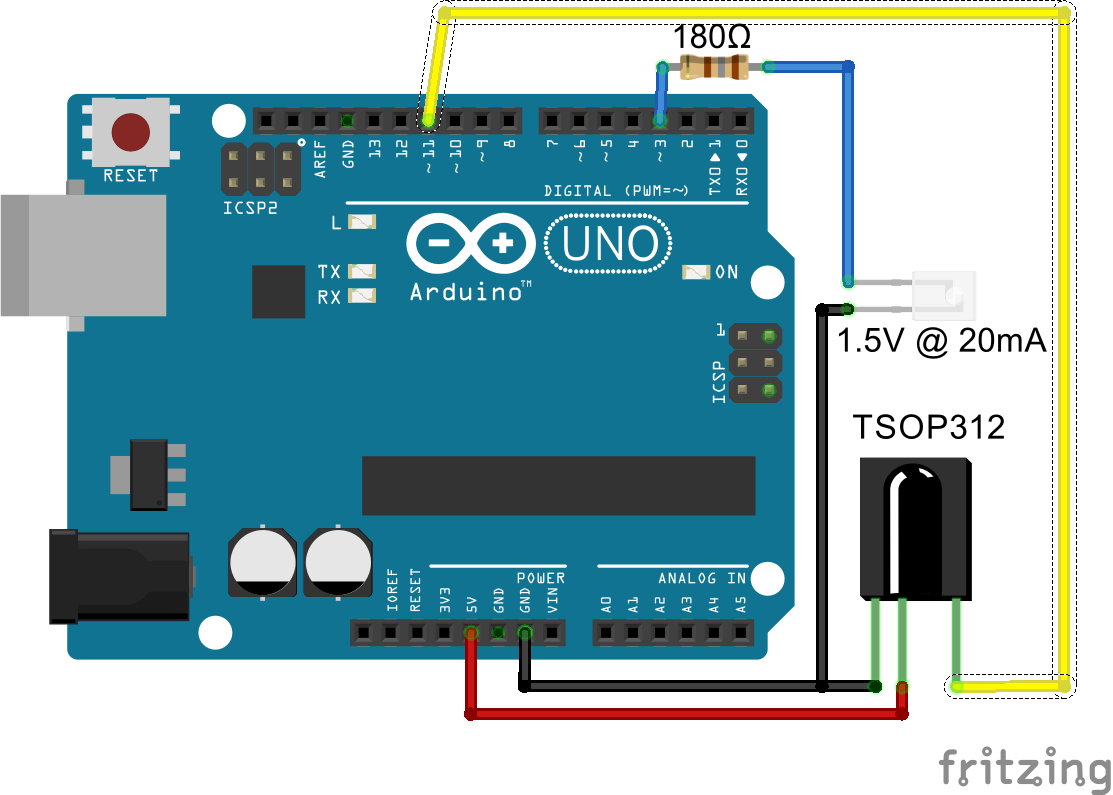

The circuit above uses a an Arduino Uno board connected to an IR receiver (in black). There are several types of IR receivers; for this tutorial is important to use a digital receiver (like the TSOP4838) and not an IR photocell . A digital receiver is sensitive to 38KHz IR signals; if it detects one, it’ll output a low voltage (0 volt), or a high one (5 volt) otherwise. A photocell, instead, acts like a variable resistor and its voltage output linearly mirrors the amount of IR light is has been exposed to. Remotes typically work on digital signals and that’s why we’ll a digital receiver.

The schematics show that I also used an IR emitter. It’s important to couple it with the right resistors; too high and it won’t turn on, too low and it will burn. IR diodes typically requires 180 Ohm resistors. Double check on your datasheets to be sure!

To decode the digital signals that the IR receiver will produce, we’ve been using a library called Arduino-IRremote, which comes with several demos and examples. Once you’ve installed the library, you can test your setup with this code.

#include <IRremote.h>

int RECV_PIN = 11;

IRrecv irrecv(RECV_PIN);

decode_results results;

void setup()

{

Serial.begin(9600);

irrecv.enableIRIn(); // Start the receiver

}

void loop()

{

if (irrecv.decode(&results))

{

Serial.println(results.value, HEX);

irrecv.resume(); // Receive the next value

}

delay(100);

}

The pin referred in line 3 must match the one you have used for your IR receiver. Line 14 decodes the raw data stored into results, either from irrecv.enableIRn() or irrecv.resume(). Once started, the program should display data when exposed to the light or a remote controller.

Step 2: Sniffing the code

So far, the setup is already able to sniff packets. irrecv.decode, in fact, shows these packets in a Human-readable format, But if we need to re-send them, the actual raw data has to be extracted and converted in a format which is compatible with irsend. The following code, inspired by this one, converts the inputs read from the receiver into a list of integer, separated by commas.

// Storage for the raw data

unsigned int rawCodes[35];

int codeLen;

void loop()

{

if (irrecv.decode(&results))

{

extractRaw(&results);

// Displays the raw codes

for (int i = 0; i < codeLen; i ++)

{

Serial.print(rawCodes[i]);

Serial.print(", ");

}

Serial.println();

irrecv.resume(); // Receive the next value

}

delay(100);

}

// Extracts the raw data

void extractRaw (decode_results *results) {

codeLen = results->rawlen - 1;

// To store raw codes:

// Drop first value (gap)

// Convert from ticks to microseconds

// Tweak marks shorter, and spaces longer

// to cancel out IR receiver distortion

for (int i = 1; i <= codeLen; i++)

if (i % 2)

// Mark

rawCodes[i - 1] = results->rawbuf[i]*USECPERTICK - MARK_EXCESS;

else

// Space

rawCodes[i - 1] = results->rawbuf[i]*USECPERTICK + MARK_EXCESS;

}

If working correctly, it should now display something like this:

1800, 400, 200, 400, 250, 350, 250, 1800, 400, 200, 400, 250, 350, 250, 1800, 400, 200, 400, 250, 350, 250,

Step 3: Sending the signal back

The numbers printed are the exact values that need to be sent to irsend.sendRaw. The only thing you’ll have to do is to store them into an array.

// Original: "1800, 400, 200, 400, 250, 350, 250,"

unsigned int code [] = { 1800, 400, 200, 400, 250, 350, 250 };

Air Swimmers have several controls: left, right, dive up and dive down. You have to sniff all of these inputs and save them into different arrays.

It is interesting to notice that some remote controllers are sending the same code, over and over again for a certain period of time. Errors in IR signals are very common, so that might be a technique to ensure that at least one of them reaches the target. If that’s an intended behaviour you want to replicate, you can use the following code.

// Sends a previously sniffer IR signal

void sendCmd (unsigned int * code, unsigned long duration)

{

unsigned long timeStart = millis();

do {

irsend.sendRaw(code, codeLen, 38); // 38KHz

delay(40);

} while (millis() <= timeStart + duration);

delay(40);

}

Line 6 is the one which actually sends the code. irsend is configured to use the pin 3.

What went wrong…

The IR sniffer works amazingly well. Adding a new Air Swimmer to the swarm is relatively easy, but it need to manually detect and configure the IR messages for each signal. We wrote a web interface to monitor and control the fish remotely, and that works as well. The only problem we experienced is the fact that Air Swimmers are incredibly challenging to control. When they are in big space, they’re really impressive. But in a small room the precision you get is too low to have a real swarm simulation. Moving them randomly doesn’t seem different at all. The real issue with them is that they’re very sensitive to air flows and temperature changes. They can suddenly move making virtually impossible to know their position without an external monitoring system. Helium naturally leaks, so after twelve hours you need to fill the balloon again. Oh, and one of the Air Swimmers exploded. I mean, it literally exploded.

Conclusion

This post explained how to hack an unknown remote controller by sniffing its IR packets. For the vast majority of applications, there is no need to understand the protocol used; messages are often independent and have no protection or timestamp. This is perfect to control a TV, a garage door or (like we did) a bunch or Air Swimmers.

The components

Providing that you already have an Arduino, this project can be done with less than $10. If you want to experiment with IR remotes, I advise you to get these 5 pairs Infrared Diode LED IR Emission and Receiver, which comes with all that you need. Alternatively, you can get the TSOP4838 which are qualitatively better. Resistors are incredibly cheap: I have used 180 Ohm ones for this tutorial.

Other resources

- Akkana Peck‘s hacked the actual remote of an Air Swimmer and integrated it with an Arduino board;

- Nano Air Swimmer: an instructable to create you own air swimmer for few dollars;

- Brain-Controller Shark Attack: a more sophisticated way of controlling an air swimmer using EEG;

- Operation Autonomous Flying Shark: a more laborious approach to decode the actual protocol of the Air Swimmers;

- Arduino-Air-Swimmers: an extension of the standard controller of the Air Swimmers. This project refers to a specific producer and may not work with all types of Air Swimmers;

- Augmenting the IR Controller for a Remote Control Flying Shark: a detailed explanation of how to decode the protocol of an Air Swimmer.

💖 Support this blog

This website exists thanks to the contribution of patrons on Patreon. If you think these posts have either helped or inspired you, please consider supporting this blog.

📧 Stay updated

You will be notified when a new tutorial is released!

📝 Licensing

You are free to use, adapt and build upon this tutorial for your own projects (even commercially) as long as you credit me.

You are not allowed to redistribute the content of this tutorial on other platforms, especially the parts that are only available on Patreon.

If the knowledge you have gained had a significant impact on your project, a mention in the credit would be very appreciated. ❤️🧔🏻

I would to implement your code to an IR-repeater. Novice as I am, can’t get it right without error messagees. I know basic Arduino coding, but that’s all.

My question How do I put these 3 sketches all together, so that it records and plays back in a loop ?

Hey!

That’s not so trivial. Mostly because I created a first Arduino sketch to “sniff” the packets used by the remote. And then another sketch that controls the actual target.

I’d start just by making a sketch that sniff the packets. The sketch in “Step 2” should work almost straight away. Alternatively you can start from one of the examples provided in the library and see how it works.

Unfortunately is very hard to help on this without seeing the code directly!

Hey Alan, nice work tho. My question is that when i decode my AC remote controller, i always get a raw data as:

—————–

DATA: 0x28 0xC6 0x0 0x8 0x8 0x3F 0x10 0xC 0x5 0x20 0x40 0x0 0x0 0x0 0x54

DATA: 40 198 0 8 8 63 16 12 5 32 64 0 0 0 84

—————————————————————————-

Now, i wanna send the codes to the AC with the help of IR sender. Which of these data will i use in my arduino code? Thanks

I think you should send this entire sequence back! 🙂

Hi Alan,

Sniffing code works properly. However for sending the recorded data frame how do you implement your “sendCmd( )” function?

Thank you in advance!

Hey!

That is discussed in Step 3!

I simply send the commands back, one by one, with some delay in between!

am looking for ready to use device that sniff signal from key fob, decode and relay.

whether ir receiver can replaced with phototransistor

Cool stuff Alan! I was able to hack my son’s train

https://home.mycloud.com/public/6bf4acfd-bad2-42eb-8b98-b1a2bb506c0c/file

with you help 🙂

Let”s say that someone drugged a woman into an unconscious state – then while in that state they put part of a wireless infrared gps in their vaginal area approx. 9 inches inside of them and put another component of the gps inside them rectally-then as a final step they placed the last piece of the gps under their scalp-they did this without consent obviously and the woman has suffered multiple health conditions as a result-which cannot be detected as infrared related injuries simply because the medical field has no knowledge of this type of thing being possible- then let’s go out on a limb and say that it was a registered sex offender who did this to the woman. Now the equipment is in the possession of the female being stalked and tracked by the sex offender because it is inside of her body-it appears that there is no way of catching the sex offender for what it is that they have done to the person illegally even though the woman has reported radiation burns to doctors and had serious vision problems (possible blindness- as a result of prolonged high infrared radiation dosage)and polyp’s where the piece of the gps system was inserted anally. What can be done to discover and catch the sex offender? he’s using his cell phone to track her and most likely has a computer inn a hidden spot-because he continues to hack her electronic devices – since the authorities have not encountered this before they are stagnant in taking any kind of action – she needs help in the worse way but doesn’t know where tgo turn to. And on her most recent cell phone that was purchased it showed that there was a communication between a computer and ir equipment. Please advise of what a person can do… your article was well written and informative. Needless to say, that the woman does not want the sex offender to be able to profit from what they have done to her- but she does feel that a gps system that could be installed on every sex offender to monitor their own where abouts could be of a great benefit to society and save many people from future abuse by violent sex offenders who do not conform and are consider non-compliant. It only geels appropriate that sex offenders should be monitored in this way since a sex offender has done thizs to an innocent person

Let”s say that someone drugged a woman into an unconscious state – then while in that state they put part of a wireless infrared gps in their vaginal area approx. 9 inches inside of them and put another component of the gps inside them rectally-then as a final step they placed the last piece of the gps under their scalp-they did this without consent obviously and the woman has suffered multiple health conditions as a result-which cannot be detected as infrared related injuries simply because the medical field has no knowledge of this type of thing being possible- then let’s go out on a limb and say that it was a registered sex offender who did this to the woman. Now the equipment is in the possession of the female being stalked and tracked by the sex offender because it is inside of her body-it appears that there is no way of catching the sex offender for what it is that they have done to the person illegally even though the woman has reported radiation burns to doctors and had serious vision problems (possible blindness- as a result of prolonged high infrared radiation dosage)and polyp’s where the piece of the gps system was inserted anally. What can be done to discover and catch the sex offender? he’s using his cell phone to track her and most likely has a computer inn a hidden spot-because he continues to hack her electronic devices – since the authorities have not encountered this before they are stagnant in taking any kind of action – she needs help in the worse way but doesn’t know where tgo turn to. And on her most recent cell phone that was purchased it showed that there was a communication between a computer and ir equipment. Please advise of what a person can do… your article was well written and informative. Needless to say, that the woman does not want the sex offender to be able to profit from what they have done to her- but she does feel that a gps system that could be installed on every sex offender to monitor their own where abouts could be of a great benefit to society and save many people from future abuse by violent sex offenders who do not conform and are consider non-compliant. It only geels appropriate that sex offenders should be monitored in this way since a sex offender has done this to an innocent person